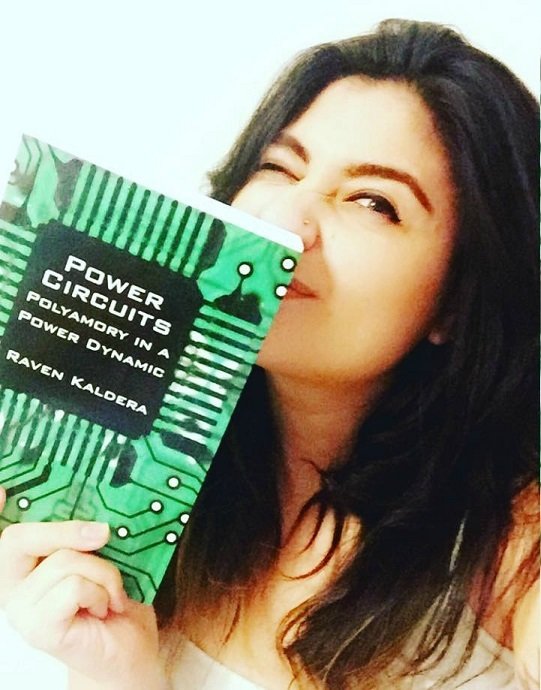

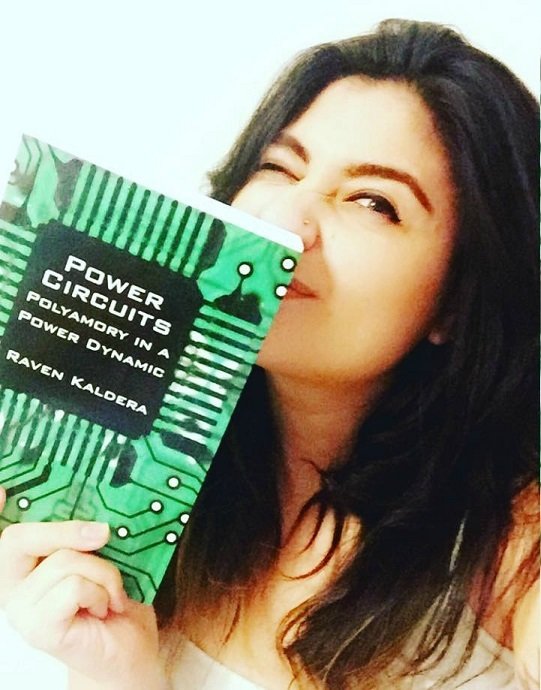

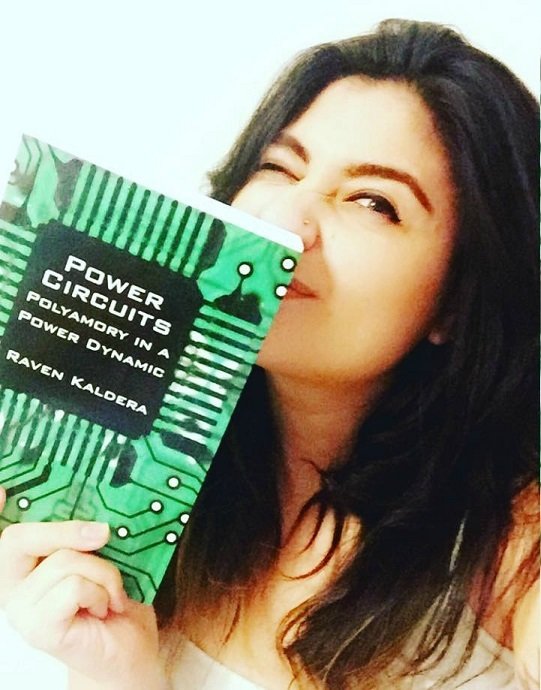

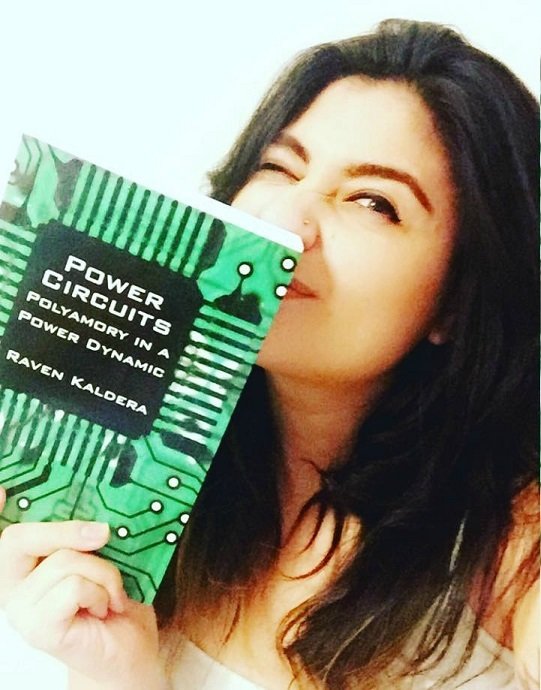

I’d fallen hard for her and wanted to give monogamy a try. In the meantime, she agreed to read “Opening Up,” one of the most famous poly how-to guides. The differences in our relationship styles were too great, however, and it became clear that neither of us could be what the other needed. After we split, I began considering poly as more of an identity than a preference.

I stumbled into polyamory: I came out as bisexual after graduating college, and the first woman I dated had a boyfriend. It was an exercise in poly mishaps: I wanted to exclusively date her rather than date them as a couple. Her boyfriend was jealous — before me, he didn’t feel threatened by his girlfriend’s relationships with women.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

This attitude toward queer women’s’ relationships is a common example of heterosexism. There’s even a word for it: the one-penis policy. I think he felt “left out” or entitled to a similar relationship with me, despite my disinterest.

Eventually, we all became involved in sexual scenarios, in part because I didn’t firmly enforce my boundaries, but mostly due to his dubious attitude toward consent.

When I began dating on OkCupid, I filtered out users who listed themselves as monogamous. I also mentioned poly upfront whenever I met people offline. Most people were open to it or had at least heard of it — OkCupid even has new poly-friendly features.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

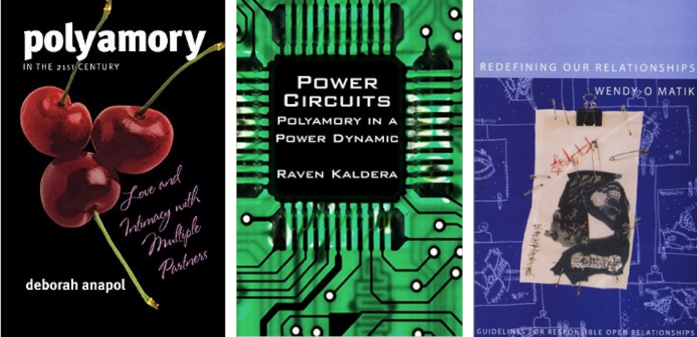

I’m still learning what works for me in my poly relationships. I’m also currently in a sex educator certification program. One of my most recent webinars was about alternative love and relationship styles.

In it, professor Rosalyn Dischiavo, a marriage and family therapist and the founder of the Institute for Sexuality Education and Enlightenment, discusses the cultivation of a poly identity in a handful of different ways.

Namely, she separates polyamory into four categories: identity, orientation, capacity, and practice. Some of these terms I understand implicitly – poly as an intrinsic part of a person’s personality with regard to relationship style, and poly as a sexual orientation. Surprisingly though, I keep coming back to the latter terms and wondering which combination of descriptors I apply to myself.

Here are some of my self-discoveries:

I value open, honest, and enthusiastic communication as a means of building trust and confronting natural feelings of jealousy. I find that open communication helps me instead of developing compersion — or deriving happiness from fulfilling your partner’s sexual and romantic desires.

In this relationship, I didn’t necessarily feel jealous — I went to their wedding and had an amazing time — but I did feel a strange loneliness. It was a combination of feeling like an outsider to their well-established love, but also gratitude and joy at being briefly included as a part of it.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:47pm PDT

The end of this relationship also taught me that no one belongs to anyone. I learned to analyze my ingrained ideas about how relationships should progress: what form they should take and what events or markers need to transpire to make the relationship valid.

The poly community calls this the “relationship escalator,” and recognizing it was incredibly liberating, though it tends to be a lesson I need to revisit again and again. It is difficult to unlearn the ways people — especially women — are socialized to expect relationships to grow and the goals (marriage, children, life partnership ’til death) we are taught to work toward without much consideration for our own individual and idiosyncratic desires.

I’m still unlearning them.

Polyamory helps me keep this in check. It reminds me that I belong only to myself. When a partner is with another partner, for example, and when I am feeling anxious, or jealous, it becomes my responsibility to examine why I feel that way.

Usually, it has to do with my ideas of self-worth and what makes my relationship valid or not, and it’s on me to confront that. Good partners, of course, will be compassionate, understanding, and supportive, but my ability to care for myself makes me feel stronger, more secure, and more self-reliant. These qualities, in turn, make me a better partner.

I used to say that sex is something you can do with your body sometimes, if you want to, but I’ve learned that sex can also be more than that – if you can ask for what you want.

Sex can be awkward and giddy and joyful: A sweetie asked tentatively, “Soooo, should we make out?” on my fourth date with him and his partner, and we spent several minutes giggling and sitting in a triangle like middle school kids playing spin-the-bottle, before we finally worked up the courage to get naked.

I’ve learned sex can be tender and kinky, the dynamic sometimes shifting from one moment to the next. I’ve also learned that kink can illuminate parts of yourself you weren’t aware of. It can be a way to give yourself over to another person, but temporarily and safely instead of entirely and without limit.

I’ve learned that sex can also be making love. It can be intimate and profound. This is a lesson I treasure.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:45pm PDT

I’ve also learned how, personally, non-monogamous relationship styles can challenge me to live more mindfully, to lean into uncertainty and prioritize curiosity and joy over fear. And, in its more difficult moments, poly has taught me about my own boundaries and limits: It has helped me realize when to say no, and how to be protective of my needs, not just the needs of others.

On the other hand, poly has also challenged me to embrace deeper levels of empathy:striving to see a situation from a metamour’s (a partner’s partner) point of view, for example, despite the uncomfortable feelings it may raise in me, is a strenuous, but valuable, exercise. Learning to tread the line between these two things is both painful and illuminating.

Maybe that’ll prove to be true. I do experience stress and emotional upheaval at times, but the rewards I encounter are greater: I am challenged to become a more self-aware person, responsible for owning and communicating my needs.

I am challenged to become more compassionate and empathetic, not only to my partners, but to the people who they love, and who love them. I am challenged to love bravely, and it is something I aspire to, every day.

title: “Christina Tesoro Explains What Being Polyamorous Has Taught Her About Love And Relationships” ShowToc: true date: “2024-09-04” author: “Dale Cooley”

I’d fallen hard for her and wanted to give monogamy a try. In the meantime, she agreed to read “Opening Up,” one of the most famous poly how-to guides. The differences in our relationship styles were too great, however, and it became clear that neither of us could be what the other needed. After we split, I began considering poly as more of an identity than a preference.

I stumbled into polyamory: I came out as bisexual after graduating college, and the first woman I dated had a boyfriend. It was an exercise in poly mishaps: I wanted to exclusively date her rather than date them as a couple. Her boyfriend was jealous — before me, he didn’t feel threatened by his girlfriend’s relationships with women.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

This attitude toward queer women’s’ relationships is a common example of heterosexism. There’s even a word for it: the one-penis policy. I think he felt “left out” or entitled to a similar relationship with me, despite my disinterest.

Eventually, we all became involved in sexual scenarios, in part because I didn’t firmly enforce my boundaries, but mostly due to his dubious attitude toward consent.

When I began dating on OkCupid, I filtered out users who listed themselves as monogamous. I also mentioned poly upfront whenever I met people offline. Most people were open to it or had at least heard of it — OkCupid even has new poly-friendly features.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

I’m still learning what works for me in my poly relationships. I’m also currently in a sex educator certification program. One of my most recent webinars was about alternative love and relationship styles.

In it, professor Rosalyn Dischiavo, a marriage and family therapist and the founder of the Institute for Sexuality Education and Enlightenment, discusses the cultivation of a poly identity in a handful of different ways.

Namely, she separates polyamory into four categories: identity, orientation, capacity, and practice. Some of these terms I understand implicitly – poly as an intrinsic part of a person’s personality with regard to relationship style, and poly as a sexual orientation. Surprisingly though, I keep coming back to the latter terms and wondering which combination of descriptors I apply to myself.

Here are some of my self-discoveries:

I value open, honest, and enthusiastic communication as a means of building trust and confronting natural feelings of jealousy. I find that open communication helps me instead of developing compersion — or deriving happiness from fulfilling your partner’s sexual and romantic desires.

In this relationship, I didn’t necessarily feel jealous — I went to their wedding and had an amazing time — but I did feel a strange loneliness. It was a combination of feeling like an outsider to their well-established love, but also gratitude and joy at being briefly included as a part of it.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:47pm PDT

The end of this relationship also taught me that no one belongs to anyone. I learned to analyze my ingrained ideas about how relationships should progress: what form they should take and what events or markers need to transpire to make the relationship valid.

The poly community calls this the “relationship escalator,” and recognizing it was incredibly liberating, though it tends to be a lesson I need to revisit again and again. It is difficult to unlearn the ways people — especially women — are socialized to expect relationships to grow and the goals (marriage, children, life partnership ’til death) we are taught to work toward without much consideration for our own individual and idiosyncratic desires.

I’m still unlearning them.

Polyamory helps me keep this in check. It reminds me that I belong only to myself. When a partner is with another partner, for example, and when I am feeling anxious, or jealous, it becomes my responsibility to examine why I feel that way.

Usually, it has to do with my ideas of self-worth and what makes my relationship valid or not, and it’s on me to confront that. Good partners, of course, will be compassionate, understanding, and supportive, but my ability to care for myself makes me feel stronger, more secure, and more self-reliant. These qualities, in turn, make me a better partner.

I used to say that sex is something you can do with your body sometimes, if you want to, but I’ve learned that sex can also be more than that – if you can ask for what you want.

Sex can be awkward and giddy and joyful: A sweetie asked tentatively, “Soooo, should we make out?” on my fourth date with him and his partner, and we spent several minutes giggling and sitting in a triangle like middle school kids playing spin-the-bottle, before we finally worked up the courage to get naked.

I’ve learned sex can be tender and kinky, the dynamic sometimes shifting from one moment to the next. I’ve also learned that kink can illuminate parts of yourself you weren’t aware of. It can be a way to give yourself over to another person, but temporarily and safely instead of entirely and without limit.

I’ve learned that sex can also be making love. It can be intimate and profound. This is a lesson I treasure.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:45pm PDT

I’ve also learned how, personally, non-monogamous relationship styles can challenge me to live more mindfully, to lean into uncertainty and prioritize curiosity and joy over fear. And, in its more difficult moments, poly has taught me about my own boundaries and limits: It has helped me realize when to say no, and how to be protective of my needs, not just the needs of others.

On the other hand, poly has also challenged me to embrace deeper levels of empathy:striving to see a situation from a metamour’s (a partner’s partner) point of view, for example, despite the uncomfortable feelings it may raise in me, is a strenuous, but valuable, exercise. Learning to tread the line between these two things is both painful and illuminating.

Maybe that’ll prove to be true. I do experience stress and emotional upheaval at times, but the rewards I encounter are greater: I am challenged to become a more self-aware person, responsible for owning and communicating my needs.

I am challenged to become more compassionate and empathetic, not only to my partners, but to the people who they love, and who love them. I am challenged to love bravely, and it is something I aspire to, every day.

title: “Christina Tesoro Explains What Being Polyamorous Has Taught Her About Love And Relationships” ShowToc: true date: “2024-10-02” author: “James Fowler”

I’d fallen hard for her and wanted to give monogamy a try. In the meantime, she agreed to read “Opening Up,” one of the most famous poly how-to guides. The differences in our relationship styles were too great, however, and it became clear that neither of us could be what the other needed. After we split, I began considering poly as more of an identity than a preference.

I stumbled into polyamory: I came out as bisexual after graduating college, and the first woman I dated had a boyfriend. It was an exercise in poly mishaps: I wanted to exclusively date her rather than date them as a couple. Her boyfriend was jealous — before me, he didn’t feel threatened by his girlfriend’s relationships with women.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

This attitude toward queer women’s’ relationships is a common example of heterosexism. There’s even a word for it: the one-penis policy. I think he felt “left out” or entitled to a similar relationship with me, despite my disinterest.

Eventually, we all became involved in sexual scenarios, in part because I didn’t firmly enforce my boundaries, but mostly due to his dubious attitude toward consent.

When I began dating on OkCupid, I filtered out users who listed themselves as monogamous. I also mentioned poly upfront whenever I met people offline. Most people were open to it or had at least heard of it — OkCupid even has new poly-friendly features.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

I’m still learning what works for me in my poly relationships. I’m also currently in a sex educator certification program. One of my most recent webinars was about alternative love and relationship styles.

In it, professor Rosalyn Dischiavo, a marriage and family therapist and the founder of the Institute for Sexuality Education and Enlightenment, discusses the cultivation of a poly identity in a handful of different ways.

Namely, she separates polyamory into four categories: identity, orientation, capacity, and practice. Some of these terms I understand implicitly – poly as an intrinsic part of a person’s personality with regard to relationship style, and poly as a sexual orientation. Surprisingly though, I keep coming back to the latter terms and wondering which combination of descriptors I apply to myself.

Here are some of my self-discoveries:

I value open, honest, and enthusiastic communication as a means of building trust and confronting natural feelings of jealousy. I find that open communication helps me instead of developing compersion — or deriving happiness from fulfilling your partner’s sexual and romantic desires.

In this relationship, I didn’t necessarily feel jealous — I went to their wedding and had an amazing time — but I did feel a strange loneliness. It was a combination of feeling like an outsider to their well-established love, but also gratitude and joy at being briefly included as a part of it.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:47pm PDT

The end of this relationship also taught me that no one belongs to anyone. I learned to analyze my ingrained ideas about how relationships should progress: what form they should take and what events or markers need to transpire to make the relationship valid.

The poly community calls this the “relationship escalator,” and recognizing it was incredibly liberating, though it tends to be a lesson I need to revisit again and again. It is difficult to unlearn the ways people — especially women — are socialized to expect relationships to grow and the goals (marriage, children, life partnership ’til death) we are taught to work toward without much consideration for our own individual and idiosyncratic desires.

I’m still unlearning them.

Polyamory helps me keep this in check. It reminds me that I belong only to myself. When a partner is with another partner, for example, and when I am feeling anxious, or jealous, it becomes my responsibility to examine why I feel that way.

Usually, it has to do with my ideas of self-worth and what makes my relationship valid or not, and it’s on me to confront that. Good partners, of course, will be compassionate, understanding, and supportive, but my ability to care for myself makes me feel stronger, more secure, and more self-reliant. These qualities, in turn, make me a better partner.

I used to say that sex is something you can do with your body sometimes, if you want to, but I’ve learned that sex can also be more than that – if you can ask for what you want.

Sex can be awkward and giddy and joyful: A sweetie asked tentatively, “Soooo, should we make out?” on my fourth date with him and his partner, and we spent several minutes giggling and sitting in a triangle like middle school kids playing spin-the-bottle, before we finally worked up the courage to get naked.

I’ve learned sex can be tender and kinky, the dynamic sometimes shifting from one moment to the next. I’ve also learned that kink can illuminate parts of yourself you weren’t aware of. It can be a way to give yourself over to another person, but temporarily and safely instead of entirely and without limit.

I’ve learned that sex can also be making love. It can be intimate and profound. This is a lesson I treasure.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:45pm PDT

I’ve also learned how, personally, non-monogamous relationship styles can challenge me to live more mindfully, to lean into uncertainty and prioritize curiosity and joy over fear. And, in its more difficult moments, poly has taught me about my own boundaries and limits: It has helped me realize when to say no, and how to be protective of my needs, not just the needs of others.

On the other hand, poly has also challenged me to embrace deeper levels of empathy:striving to see a situation from a metamour’s (a partner’s partner) point of view, for example, despite the uncomfortable feelings it may raise in me, is a strenuous, but valuable, exercise. Learning to tread the line between these two things is both painful and illuminating.

Maybe that’ll prove to be true. I do experience stress and emotional upheaval at times, but the rewards I encounter are greater: I am challenged to become a more self-aware person, responsible for owning and communicating my needs.

I am challenged to become more compassionate and empathetic, not only to my partners, but to the people who they love, and who love them. I am challenged to love bravely, and it is something I aspire to, every day.

title: “Christina Tesoro Explains What Being Polyamorous Has Taught Her About Love And Relationships” ShowToc: true date: “2024-10-12” author: “Bobby Gurule”

I’d fallen hard for her and wanted to give monogamy a try. In the meantime, she agreed to read “Opening Up,” one of the most famous poly how-to guides. The differences in our relationship styles were too great, however, and it became clear that neither of us could be what the other needed. After we split, I began considering poly as more of an identity than a preference.

I stumbled into polyamory: I came out as bisexual after graduating college, and the first woman I dated had a boyfriend. It was an exercise in poly mishaps: I wanted to exclusively date her rather than date them as a couple. Her boyfriend was jealous — before me, he didn’t feel threatened by his girlfriend’s relationships with women.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

This attitude toward queer women’s’ relationships is a common example of heterosexism. There’s even a word for it: the one-penis policy. I think he felt “left out” or entitled to a similar relationship with me, despite my disinterest.

Eventually, we all became involved in sexual scenarios, in part because I didn’t firmly enforce my boundaries, but mostly due to his dubious attitude toward consent.

When I began dating on OkCupid, I filtered out users who listed themselves as monogamous. I also mentioned poly upfront whenever I met people offline. Most people were open to it or had at least heard of it — OkCupid even has new poly-friendly features.

Christina Tesoro – Christina Tesoro

I’m still learning what works for me in my poly relationships. I’m also currently in a sex educator certification program. One of my most recent webinars was about alternative love and relationship styles.

In it, professor Rosalyn Dischiavo, a marriage and family therapist and the founder of the Institute for Sexuality Education and Enlightenment, discusses the cultivation of a poly identity in a handful of different ways.

Namely, she separates polyamory into four categories: identity, orientation, capacity, and practice. Some of these terms I understand implicitly – poly as an intrinsic part of a person’s personality with regard to relationship style, and poly as a sexual orientation. Surprisingly though, I keep coming back to the latter terms and wondering which combination of descriptors I apply to myself.

Here are some of my self-discoveries:

I value open, honest, and enthusiastic communication as a means of building trust and confronting natural feelings of jealousy. I find that open communication helps me instead of developing compersion — or deriving happiness from fulfilling your partner’s sexual and romantic desires.

In this relationship, I didn’t necessarily feel jealous — I went to their wedding and had an amazing time — but I did feel a strange loneliness. It was a combination of feeling like an outsider to their well-established love, but also gratitude and joy at being briefly included as a part of it.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:47pm PDT

The end of this relationship also taught me that no one belongs to anyone. I learned to analyze my ingrained ideas about how relationships should progress: what form they should take and what events or markers need to transpire to make the relationship valid.

The poly community calls this the “relationship escalator,” and recognizing it was incredibly liberating, though it tends to be a lesson I need to revisit again and again. It is difficult to unlearn the ways people — especially women — are socialized to expect relationships to grow and the goals (marriage, children, life partnership ’til death) we are taught to work toward without much consideration for our own individual and idiosyncratic desires.

I’m still unlearning them.

Polyamory helps me keep this in check. It reminds me that I belong only to myself. When a partner is with another partner, for example, and when I am feeling anxious, or jealous, it becomes my responsibility to examine why I feel that way.

Usually, it has to do with my ideas of self-worth and what makes my relationship valid or not, and it’s on me to confront that. Good partners, of course, will be compassionate, understanding, and supportive, but my ability to care for myself makes me feel stronger, more secure, and more self-reliant. These qualities, in turn, make me a better partner.

I used to say that sex is something you can do with your body sometimes, if you want to, but I’ve learned that sex can also be more than that – if you can ask for what you want.

Sex can be awkward and giddy and joyful: A sweetie asked tentatively, “Soooo, should we make out?” on my fourth date with him and his partner, and we spent several minutes giggling and sitting in a triangle like middle school kids playing spin-the-bottle, before we finally worked up the courage to get naked.

I’ve learned sex can be tender and kinky, the dynamic sometimes shifting from one moment to the next. I’ve also learned that kink can illuminate parts of yourself you weren’t aware of. It can be a way to give yourself over to another person, but temporarily and safely instead of entirely and without limit.

I’ve learned that sex can also be making love. It can be intimate and profound. This is a lesson I treasure.

A photo posted by ⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀NB Genders United (@demigenders) on Apr 14, 2016 at 1:45pm PDT

I’ve also learned how, personally, non-monogamous relationship styles can challenge me to live more mindfully, to lean into uncertainty and prioritize curiosity and joy over fear. And, in its more difficult moments, poly has taught me about my own boundaries and limits: It has helped me realize when to say no, and how to be protective of my needs, not just the needs of others.

On the other hand, poly has also challenged me to embrace deeper levels of empathy:striving to see a situation from a metamour’s (a partner’s partner) point of view, for example, despite the uncomfortable feelings it may raise in me, is a strenuous, but valuable, exercise. Learning to tread the line between these two things is both painful and illuminating.

Maybe that’ll prove to be true. I do experience stress and emotional upheaval at times, but the rewards I encounter are greater: I am challenged to become a more self-aware person, responsible for owning and communicating my needs.

I am challenged to become more compassionate and empathetic, not only to my partners, but to the people who they love, and who love them. I am challenged to love bravely, and it is something I aspire to, every day.